Lawyer's true-crime book explores how he defended a neurodivergent client charged with murder

Updated: In 1997, in the small town of Ringgold in northwest Georgia, a reclusive man was accused of keeping his wife captive in his home and murdering her.

Alvin Ridley—a Zenith television salesman and repairman—was often castigated by others in the neighborhood for his lack of personal hygiene, living in a rundown, cockroach-infested home and his seemingly non-emotive, paranoid way of speaking, all of which made him an easy target.

McCracken Poston Jr., a politician-turned-defense attorney, was fresh off a divorce and a congressional seat loss. But he took on the case and was able to dig deep into Ridley’s unstable mind to determine that he was not a killer. Ridley was eventually found not guilty.

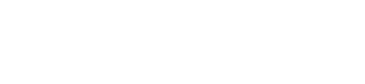

A quarter of a century later, Poston has penned the nonfiction book Zenith Man: Death, Love, and Redemption in a Georgia Courtroom, which tells the story of the quirky man, the death of his wife and the trial that shocked his small town. In May, the book was nominated for CrimeCon’s true-crime book of the year award. CrimeCon, a weekend event for true-crime fans, will announce the winner of the best book during its annual event, taking place May 31-June 2 in Nashville, Tennessee.

The ABA Journal spoke with Poston on Zoom to learn about how he got to know and defend the man who everyone else avoided—and how other attorneys can help when it comes to neurodivergent clients.

Why was this case so difficult?

Everybody knew everybody in that town. Alvin provided us with our first color TV, and my oldest sister went to high school with him. He was neurodivergent and later diagnosed with autism, but this wasn’t diagnosed at the time. Two days after his wife’s death, Alvin started showing up at the same intersection near my office. Three days after he planted himself in the same spot, I initiated conversation and became his lawyer. I realized Alvin was very transactional, so I started paying him for his cooperation. It took over a year for him to allow me into his house. Alvin was constantly countering my legal advice, which was extremely frustrating and difficult. He didn’t trust me, and I don’t think he trusted anyone.

How did you connect with the man who trusted no one?

I truly knew that Alvin was innocent (after dealing with him for 15 months). I became personally invested in the case, to the point where judges were saying we deserved each other. I very slowly gained compassion. Five weeks before the trial, he showed up at a Christmas festival in a full Santa outfit that was mothball-eaten, and he was handing out candy. I recognized him by his scent and by his hands. Alvin doesn’t bathe because he doesn’t like the sensation of water on his skin, but I didn’t realize that. I suggested he needed to take a shower, and I immediately felt bad about it. Something inside of me was telling me all along, “This guy can’t help it.”

“Today, armed with more knowledge, I don’t think this would have happened,” McCracken Poston Jr. says of the events he recounts in Zenith Man.

“Today, armed with more knowledge, I don’t think this would have happened,” McCracken Poston Jr. says of the events he recounts in Zenith Man.How did having a neurodivergent person on trial for murdering his wife affect the outcome of the case?

No one knew much about neurodivergent people 25 years ago. They were hinging so much of this on his emotions that they felt should be different when his wife died. Today, armed with more knowledge, I don’t think this would have happened. There are 5.5 million adults who have never been diagnosed as neurodivergent, and the entire criminal justice system needs to be more aware. If he had been properly diagnosed, it could have eased a lot of conflict. I was barking orders at a neurodivergent man, and Alvin would not stand for it at all, and that created our conflict.

Why are you continuing to promote this case 25 years later, and what should other attorneys take from it?

Alvin gave me a second act in life—and maybe a third. He’s 82 now, and we go to lunch at least twice a week. My secretary and I are his main contacts to the neurotypical world, and we try to help him navigate it while he maintains his independence as long as possible. There are other innocent people like Alvin who might end up imprisoned for the wrong reasons. Alvin was very much interested in something I said after the verdict came through. He was ready to rebuild his reputation in the community, and I told him, “If you don’t define your situation, somebody else will define it.” If he wanted the full story out there, I needed to write it.

Updated May 15 at 8:11 a.m. to clarify that McCracken Poston Jr. knew that Alvin Ridley was innocent after dealing with him for 15 months.